By Jenny Stein

Following a volcanic eruption, local communities understandably have more pressing concerns than ensuring a sample of ash gets sent to a lab. But that sample will provide crucial insight into the extent and types of hazards people will be exposed to in the eruption aftermath.

Carol Stewart is a researcher with the Resilience to Nature’s Challenges National Science Challenge, Associate Professor of Environmental Health at Massey University, co-director of the International Volcanic Health Hazard Network (IVHHN) and member of the New Zealand Volcanic Science Advisory Panel (NZVSAP). Her specialty is determining the health hazards of volcanic ash and she has been involved in the responses to numerous eruptions, including Ambae volcano in Vanuatu, La Soufrière in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Cumbre Vieja in the Canary Islands, and Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai in Tonga.

“Ash from every eruption is different, so each time you’ve got to go in and analyse it,” Carol explains. “The most important characteristic is the grain size distribution. The finer the grains are on the ground, the higher the potential for them to be picked up by wind and breathed deep into the lungs.”

While ash coarser than 0.1mm diameter quickly drops out of the air and is unlikely to be inhaled, ash between 0.1 and 0.01mm diameter will deposit in the eyes, nose and throat, causing irritation and a cough. Ash particles finer than 0.01mm diameter travel deeper into the lungs, worsening the symptoms of people with existing lung problems, potentially making it difficult to breathe.

Many people also worry about the contamination of food and water supplies. However, in Carol’s experience, this risk is much further down the list.

“The biggest risk of all is having no water, because then all the sanitation consequences become a lot worse. The next thing to worry about is the microbiological safety of the water; you’ve got to make sure people have a means of treating it. Then, thirdly, you can start worrying about the chemical composition of the water.”

Fortunately, chemicals leaching out of volcanic ash usually affect water’s taste long before reaching toxic concentrations, and even then, short term exposure is unlikely to do serious harm. But there are exceptions.

“You’ve always got to be aware that you might get some really freaky ash composition which doesn’t make water taste nasty but may be quite toxic.”

While the benefits of having an ash sample to analyse are clear, advice is often needed long before such analyses can be performed.

“It’s really hard because getting an ash sample is not a priority for anyone else except us (scientists). In the early days of messaging there’s always a real tension between getting something out rapidly with incomplete information, versus waiting for better information that may come too late.”

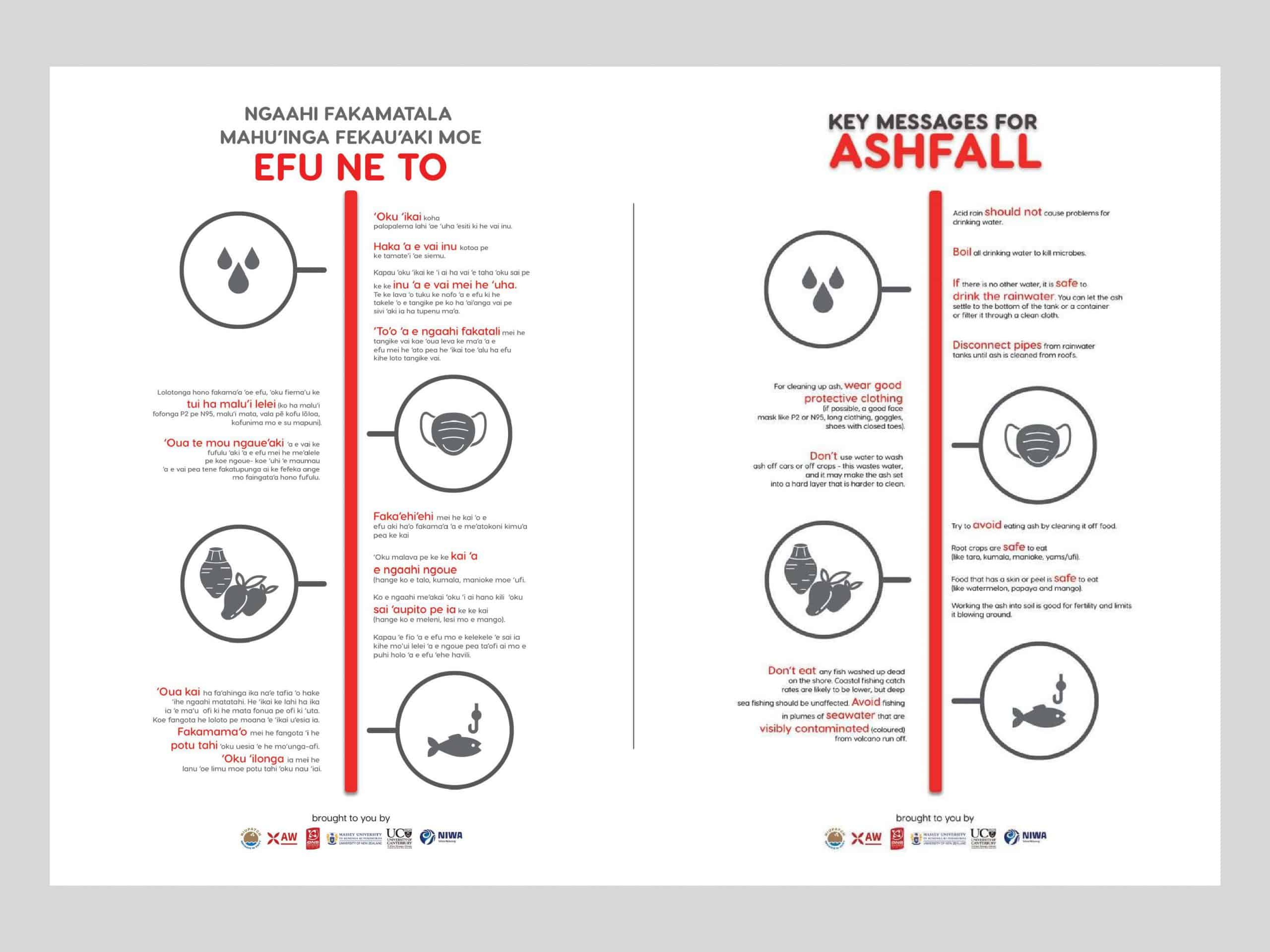

After the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption on January 15, Carol and her colleagues were approached by Tongan community leaders here in New Zealand who wanted simple, practical advice about precautionary measures that could be taken by their friends and family back home. Carol and colleagues at the University of Canterbury, GNS Science and NIWA got to work preparing messages that were translated into Tongan by community leader Emeline Afeaki-Mafile’o and given to Massey University design student Matt Luani to be turned into infographics. Associate Professor Siautu Alefiao of Massey University’s Niupatch organised for a thousand fliers to be printed and added to aid boxes being sent to Tonga.

“It only took about three or four days, it was really fast,” Carol says, reflecting on the team’s efforts.

Then, on January 22, an all-important ash sample arrived, collected by the New Zealand Defence Force from beside the runway during their delivery of aid supplies.

“It was not the most pristine looking sample I’ve ever seen…but we all got to work on that.”

Carol’s colleague, Professor Shane Cronin of the University of Auckland, met the sample at Whenuapai airport and sent subsamples round the country for analysis. Within 48 hours the IVHHN/NZVSAP team had produced a peer-reviewed report on the grainsize distribution, with chemical analyses reported a few days later.

More samples soon arrived from other locations, including an important sample from the capital Nuku’alofa, collected by Taaniela Kula of Tongan Geological Services.

“It turned out that the ash was actually not acidic, which is really unusual. It was also very low in fluoride, which was a big relief because fluoride is one of the main concerns.”

While beneficial in small doses (such as fluoridated water and toothpaste), fluoride can be deadly if ingested in sufficient quantities. Livestock that eat feed covered in even a light amount of fluoride-rich ash may develop lethal fluorosis—as happened after the 1995 eruption of Ruapehu, when over two thousand sheep died.

With Ruapehu currently showing signs of renewed activity, and numerous other active volcanoes on and around our shores, there’s sure to be more volcanic eruptions in Aotearoa New Zealand in future. When that time comes, Carol and the teams at IVHHN and NZVSAP will be ready.

“It’s really nice to be useful in a crisis like this,” reflects Carol. “And Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai was an amazing chance to rehearse our systems.”

You can view a pdf of the infographic sent to Tonga here.