Serious games offer a playful yet powerful way for scientists, engineers, policy makers, and community members to find the best solutions to complex problems. Something seemingly as simple as deciding whether to rebuild a road damaged by coastal erosion requires a multitude of considerations, ranging from who and how many people depend on the road, to how much it will cost to rebuild, and how long the road is likely to last before being washed out again if repaired. It can be hard to identify and examine other alternatives whilst taking different stakeholder’s perspectives, knowledge and values into account. Serious games offer a fast and effective way to explore options and test-run decisions, meaning they may have a serious role to play in climate adaptation planning.

“Games are good at getting people started. They’re different from scenario exercises in that the more pure kind of ‘play’ allows for more creative experimentation and disruptive thinking,” says Eleanor Chaos, a PhD candidate at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington co-funded by Resilience to Nature’s Challenges (RNC). She is investigating how serious games can be used as a tool to help with decision-making for climate change adaptation and says games are good at getting people to engage with difficult problems, by taking people out of their normal workday and—crucially—providing a ‘safe-to-fail’ space.

“Serious games provide a situation where people can change their thinking. You can try things out and there aren’t any consequences; you don’t lose money and nobody dies!” Eleanor says.

Another key aspect of serious games is encouraging people to approach problems from different perspectives through roleplay. For example, an engineer might play the role of a policy maker in-game, a policy maker the role of a community leader, and a community leader might play the role of an engineer.

“Both in-game roleplaying and playing with people from different roles or backgrounds helps the players better understand each other’s thinking and perspectives,” Eleanor says.

It’s a novel approach that ‘rehearses’ decisions people will often need to one day make in their real roles, in real life.

One of the games featured in Eleanor’s study was developed by the Department of Conservation, to role-play scenarios for a bridge wash-out on a walking track and explore what would be the best remediation option for walkers, tourism operators and local communities.

“Since they designed the game, one of the bridges actually did wash out, so it was a matter of life imitating the game,” Eleanor says.

Such occurrences are more likely to happen than not, as another key feature of serious games is their foundation in scientific, evidence-based predictions for future scenarios.

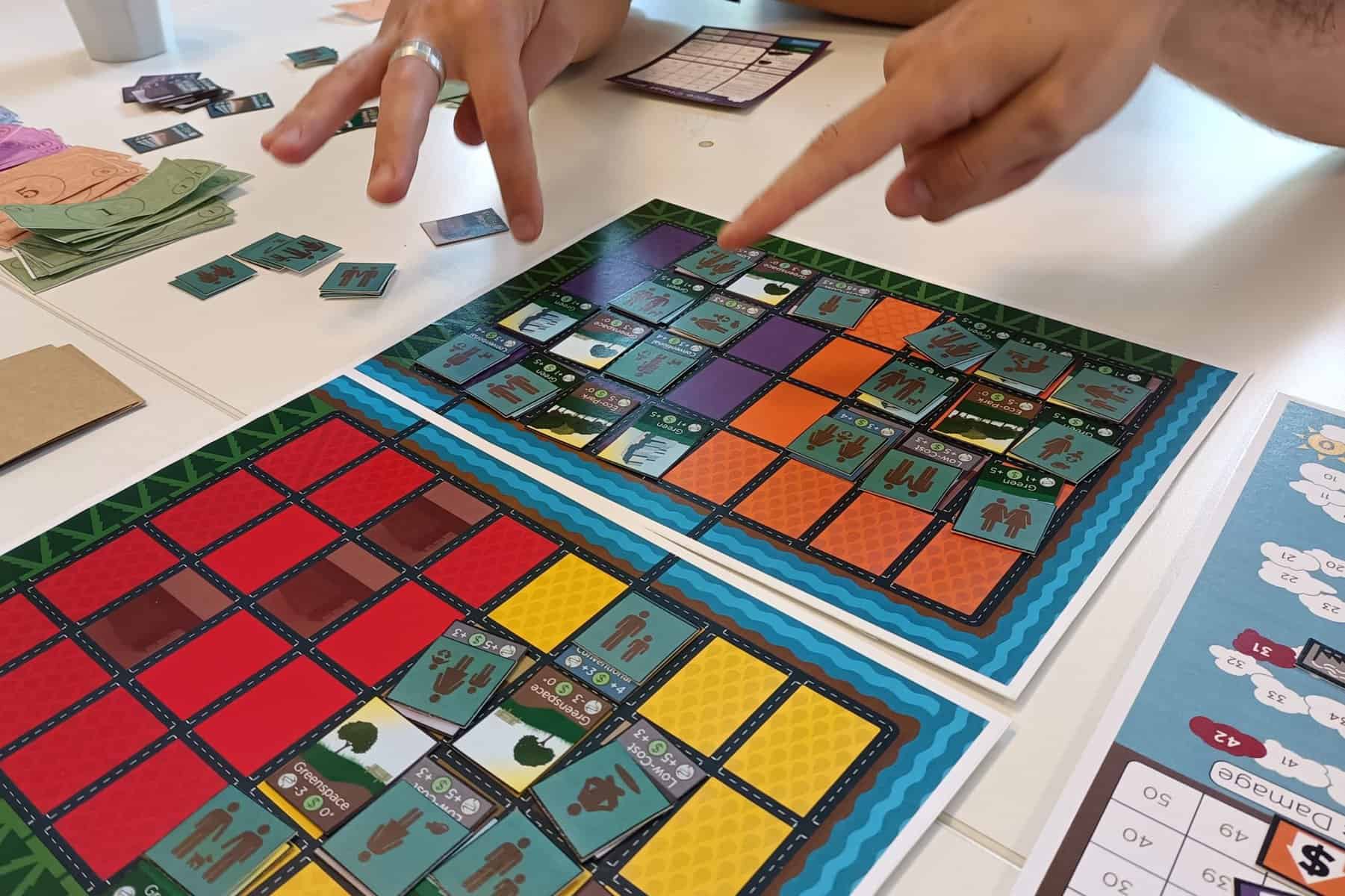

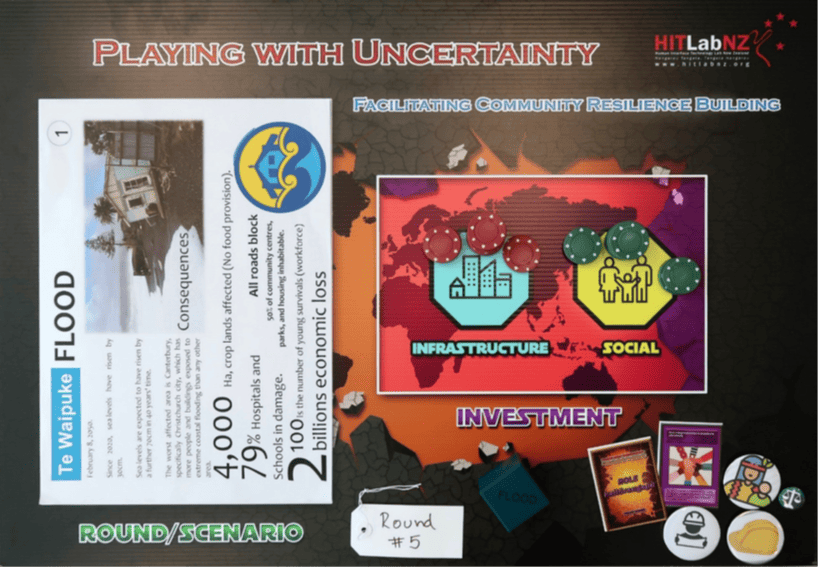

Bryann Avendano is another RNC-funded PhD candidate, based at the University of Canterbury, who is working with HITLab (the Human Interface Technology Lab) to develop his own serious game. His game is based on predicted future sea level rise scenarios in Lyttleton over the next 80 years and is designed to help stakeholders decide where and whether to invest in social and/or infrastructural assets.

“Whether to invest is always a planning problem,” Bryann says. “Do we need more stopbanks? Or do we need to spend more on educating people? What if engineers, scientists, policy makers and community leaders could play out scenarios and see what could happen if they decide this or that? That’s what the game is about.”

Consisting of six rounds played over one hour, Bryann’s game requires players to negotiate investment choices and review decisions made after each round. They discuss what the benefits and drawbacks are, all the while trying to get the best possible outcome for their role and the community. Bryann calls it ‘Playing with uncertainty’.

“I add a little bit of tension by saying “Hey guys, we have ten minutes to decide because the Prime Minister is asking ‘What’s the decision?’…and then I role the disaster dice.”

Rolling the disaster dice changes the scenario by introducing a flood or other event that requires everyone to make new decisions and play out the impacts of decisions they previously made. It’s a fun take on a serious issue (or a serious take on having fun) that is proving popular and worthwhile.

“Most community engagement initiatives consist of a workshop with an expert talking for three hours and people are just waiting for the food. Instead, we spend one hour, everyone plays, we gather the data, and we’re done. Everyone is happy and everyone wants to repeat it, which is good.”

The hardest part is often convincing busy professionals that’s it’s worth taking an hour out of their day to ‘play’ a serious game.

“New Zealand is very new to serious games,” Bryann says, comparing us to Europe where there is already a large community of companies and citizen science initiatives using serious games to tackle resilience and sustainability problems, engage with communities, and communicate risk. But Bryann says we have an opportunity to become a world leader in the world of serious games:

“We’re creating a unique platform to play with the uncertainties of climate change, and I invite all New Zealanders to play!”

Eleanor Chaos is a PhD candidate at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington, co-supervised by Dr Judy Lawrence and Dr Paula Blackett (NIWA).

Bryann Avendano is a PhD candidate at Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha University of Canterbury, co-supervised by Professor Mark Milke and Associate Professor Heide Lukosch.