On Friday 5 March 2021, communities across the North Island were shaken awake by a M7.3 earthquake located 175km offshore, northeast of Gisborne. It was the first of three large earthquakes along the Kermadec Trench that morning, generating a series of overlapping tsunami that would arrive in New Zealand within hours and continue to generate unusual wave activity for several days. Fortunately, these events did not result in any major inundation along our coast, but it highlighted the need for coastal communities to be prepared for these rare but potentially devastating phenomenon.

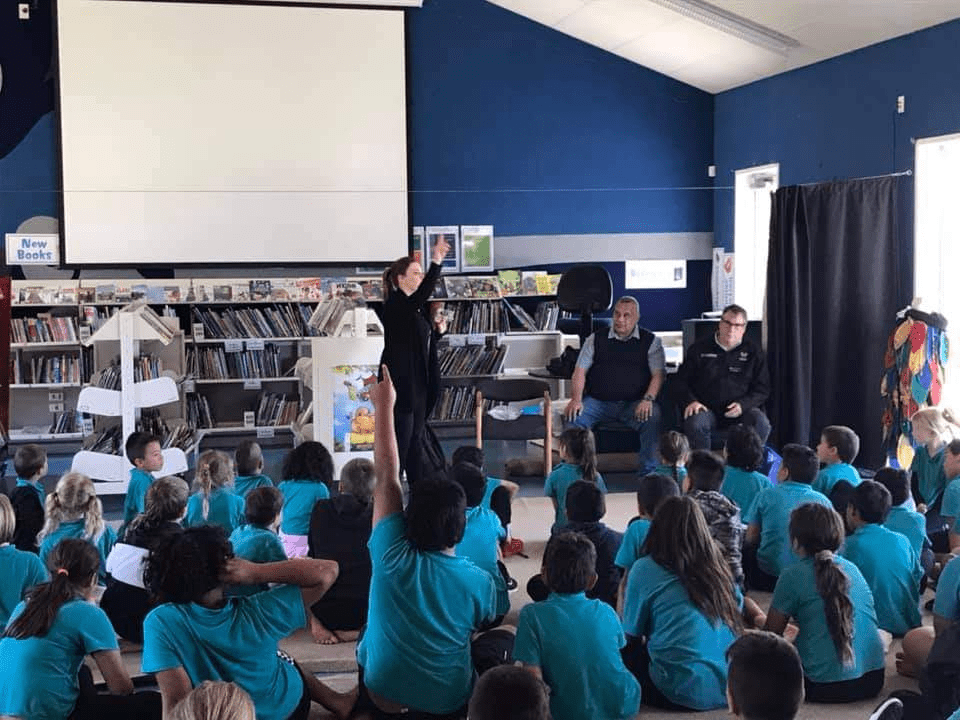

Resilience Challenge researcher and GNS Science/Massey University social scientist Lucy Kaiser (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha), Matua Kelvin Tapuke (Te Ātiawa , Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāi Tai, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki , Ngāti Porou, Te Whānaua -a-Apanui, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Ngāi Tūhoe, Te Whakatōhea, Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Raukawa, Toa Rangatira) and Professor David Johnston of Massey University were interested in finding out how coastal communities in the Tairāwhiti region had responded to the March 5 events. Engaging with ten schools, they were quickly struck by how well prepared many schools and communities had been.

“A lot of those resilience skills and activities we encourage people to use after a disaster, like checking on your friends, family and community, and being prepared to find food because you might be cut off for several days, that stuff is already happening in these rural communities,” Kaiser says.

Most schools they spoke to had decided not to open after the first earthquake on March 5 and so had not needed to evacuate. One school that did was Matatā Primary School. In the midst of a school function when alerted to the tsunami threat, they simply took all the food they had prepared up the hill with them and settled in for the day. Many people in the surrounding community followed.

“It’s a good example of communities taking the lead from schools and shows how crucial schools are for community preparedness. If schools do the right thing, you’ll hopefully get the community following along to safety as well.”

Reports from schools also highlighted the value of practice drills in helping people become more likely to respond appropriately when earthquakes or tsunami do occur.

“At one school, their first tsunami evacuation hīkoi upset some of the kids, but then they were calm when it was for real because they knew what to do. This is one of the reasons Tsunami Hīkoi and Shakeout gets practiced every year.”

The ultimate aim of the team’s research is to determine what lessons can be learned from the resilience of rural communities, and what information and resources they need.

“Rural communities have different resources, skills and needs compared to urban communities so it’s really important we understand their experiences in earthquake and tsunami preparedness and investigate what additional support may be useful for them. We could sit in our offices and put together a programme of what we think would be useful, but it wouldn’t necessarily be fit for purpose.”

While commending the development of te reo resources for kura kaupapa Māori schools by emergency management organisations, Kaiser says their research shows that more specific resources are needed.

“Between different iwi and hapū there are differences in dialect and pūrākau (traditional stories) that define how they respond to and understand tsunami. Our kaupapa is really around making sure our tamariki are prepared and that we’re working with kura and other schools, to contextualise emergency management and preparedness information within their own school kaupapa and within their own mātauranga Māori.”

Another aim of the project is to promote emergency management as a viable career path for rural rangatahi (young people).

“There’s not a lot of visibility of people working in this space, particularly Māori and wāhine, so it’s a really great opportunity to talk to kids about how much we love what we do and how they can make an impact in protecting their communities.”

Asked what the next steps are, Kaiser says the way is clear:

“It’s creating and maintaining relationships between researchers, schools and emergency management. The most effective mechanism is if good, solid messaging comes from trusted sources in communities but the strength of relationships and positive outcomes of working together are very people and time dependent. You need to be showing your face, kanohi ki te kanohi, and be willing to listen and adapt to what the priorities of communities and schools are. Focusing on that is the way forward for ensuring our communities are prepared for future disasters.”

This work has been co-funded by the Resilience To Nature’s Challenges’ Ākina Te Tū Kaupapa Māori Research Fund and Resilience, Policy and Governance programme, QuakeCoRE and Strategic Science Investment funding from GNS Science.