An economic investigation of disaster insurance

25/09/2018

By Ilan Noy

The Christchurch Earthquake of 2011 was the most insured earthquake ever, anywhere, with 98% of Christchurch properties being insured when the quakes occurred (Nguyen and Noy, 2017). In comparison, a recent New York Times article stated that only 13% of houses in California are currently insured. Yet the public’s view of the way our public-private insurance system functioned in the aftermath of the quake is dim, at best.

What were the impacts of all this insurance cover during the recovery in Christchurch? How will our insurance system deal in the future with weather risk as climate change begins to bite more? And what can we do to fix any problems? These are some of the questions being asked by Resilience to Nature’s Challenges’ Economics Toolbox researchers.

In July 2018, the Earthquake Commission (EQC) reported that it was still processing 3,476 claims for damage from the 2010-2011 Canterbury Earthquake Sequence (CES). During that month, it closed 811 claims, but also received 767 new claims associated with the CES (some for previously completed repairs). So, in July, the net reduction in the number of open claims was 44. Yet, the CES was the most heavily insured event in history, and as such our insurance system managed to shield New Zealand from much of the financial consequence of the earthquakes. The cost of the earthquake recovery was largely transferred overseas (to insurance companies across the Tasman, and further afield to reinsurers in London and other international financial centres).

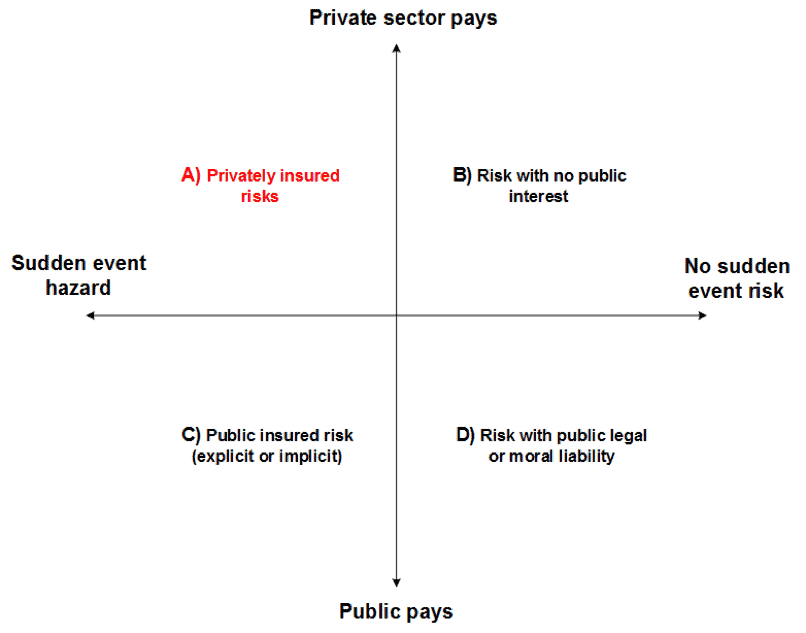

When insurance functions properly it manages to transfer the financial risk from individuals, families, and companies, to the financial markets. In addition, the best disaster insurance systems also manage to incentivise risk reduction ex ante and to speed up recovery ex post. It should also encourage and enable investment in productive opportunities and protect the most vulnerable in our society from falling into poverty in the aftermath of an event. While our insurance system did achieve its first goal, it delivered less successfully on the other four.

In the first years of the Resilience Challenge, our team (Ilan Noy, together with post-grad students Cuong Nguyen, Sally Owen, Jacob Pastor-Paz, Polly Poontirakul, and Belinda Storey) has documented how and when our insurance system does and does not deliver on its promise. This research agenda included examining both the Earthquake Commission insurance, the private residential insurance that sits on top of the EQC cover, and commercial insurance (both for commercial property and business interruption).

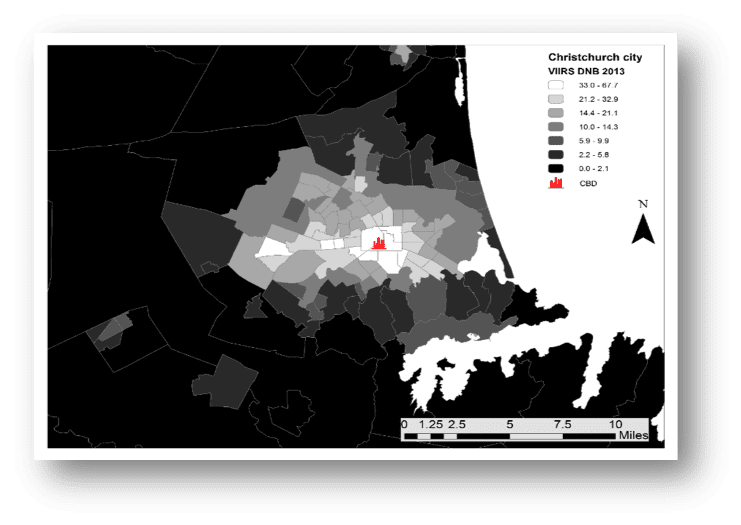

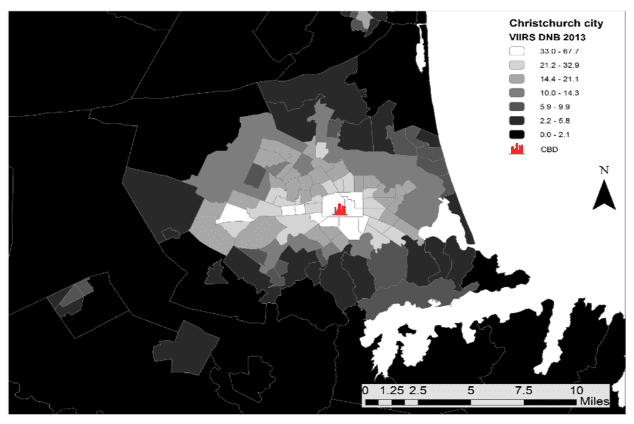

For example, we documented that EQC insurance payments assisted in the recovery of residential areas of the city, which was measured by night-time luminosity as captured by satellites. More surprisingly, this research also documented that cash payments were more conducive to local economic recovery, as measured by nightlights, than house repairs done through the managed repair programme (though we do not know whether the damage was repaired with this cash). In another research project, we documented that firms that had insurance and were paid promptly recovered much better than both firms with no insurance and firms that had insurance but whose claim payments were delayed. Unexpectedly, we found that there was no observable difference in recovery trajectories between those firms that had no insurance at all, and those who did, but whose payments were belated.

In a remarkably less lauded government initiative, the presence of so much insurance helped us (tax and rate payers) by funding most of the costs associated with the Residential Red Zone programme. The programme was the largest ‘managed retreat’ effort undertaken in a developed country to reduce risk exposure, through which residents were ‘bought out’ from risky Red Zone areas of the city. We are now examining the choices Red Zone property owners made, and determining what lessons we can learn from that programme for the future implementation of managed retreat plans elsewhere.

Based on the insights gained from this research, we recently made two submissions to the government for its Insurance Law Review. These submissions were written together with Roger Sutton, ex-CEO of CERA, Leanne Curtis, director of Breakthrough Services in Christchurch, and Samuel Becher, a Professor of Consumer Law. In the submissions, we advocated for several changes and additions to the Insurance Law; changes that we think will make New Zealand more ‘resilient to nature’s challenges.’