Investigating coastal archaeological vulnerability in Aotearoa

Tēna koutou katoa

Ko Crocodile te awa

E hono ana ahau ki Royal Oak Tāmaki Makaurau

Ko Ben Jones tōku ingoa

He Kairangahau ahau ki te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau

He mihi nui, he mihi aroha!

I was born in South Africa in a small rural community. At the age of 15 I came to Aotearoa and made Auckland home. As an immigrant you attempt to learn everything you can, every bit of slang, idiosyncrasy and the finer points of ‘yeah nah, nah yeah’.

I formed a connection with Aotearoa through its history. Undertaking my undergraduate and Masters research at the University of Auckland enabled me to dig deeper into Aotearoa’s past. Stumbling into archaeology unpacked the scope and complexity of the human past, especially the coastal heritage of Pacific Islands. For my Masters I investigated how rice agriculturists impacted an intensive pre-contact agricultural system in Hawai’i. I was hired as a GIS technician job based on the techniques I developed using applications of GIS and LiDAR during my Masters. My role in the project was to digitise and service online all the maps produced by the Crown. (over 20,000 maps, 5000 of them geo-referenced). Cataloguing the cartographic history of Aotearoa yielded a knowledge base useful for my PhD research and wider public use.

For the past 5 and a half years I have been working as a professional archaeologist in Aotearoa and in Australia. The takeaway from this role for me was the engagement with iwi and hapū who have an ancestral connection to the archaeology I have investigated. The best encapsulation of this is the proverb ‘Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: ‘I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past’. Iwi, hapū and local communities are faced with potentially losing these places due to sea level rise driven by climate change.

My project

My PhD project stems from the Coastal Hazards research programme within the Resilience to Nature’s Challenges National Science Challenge | Kia manawaroa – Ngā Ākina o Te Ao Tūroa. Thanks to my great supervisory team Mark Dickson, Emma Ryan, Murray Ford and Dan Hikuroa. The overall aim of the Coastal Hazards programme is to resolve physical coastal hazard questions faced by communities around Aotearoa. Incremental sea-level rise (SLR) and changing wave patterns will fundamentally reshape our coastlines and re-define Aotearoa’s future coastal hazards. One of the coastal assets at risk is cultural heritage, particularly archaeological sites related to Māori occupation.

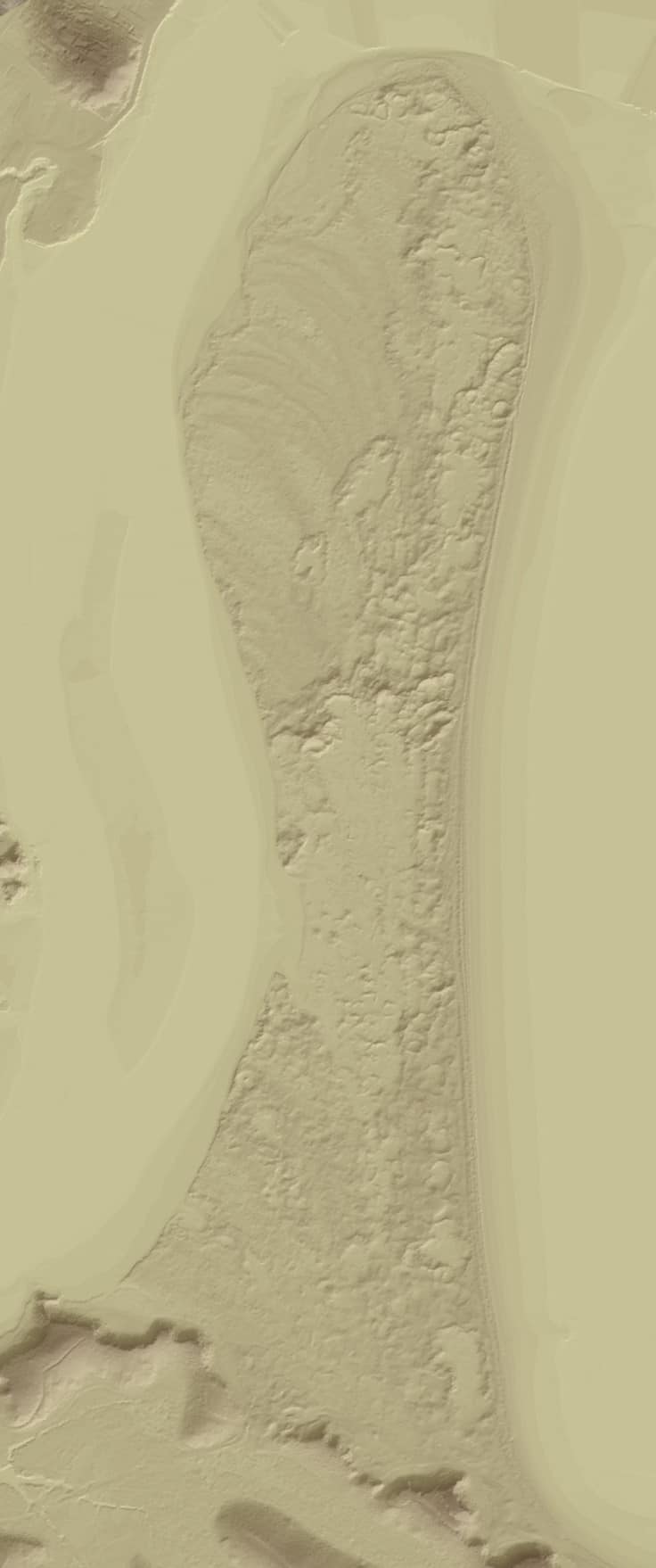

Many of these sites are located close to coastlines and are vulnerable to coastal hazards exacerbated by SLR. Factors of particular significance include large tidal ranges and storm surges especially in shallow harbours, river mouths and estuaries. Coastal erosion is a key threat to the preservation of archaeological sites, either exposing sites to future destruction and/or destroying exposed sites. 37.3% of archaeological sites recorded are within 500m of the coast. Further research to investigate the vulnerability of coastal archaeological sites is needed, in order to understand what that percentage means at different national, regional and local geographic scales. Understanding the impact and the scale of the problem is important, both from a scientific and cultural perspective, because these sites hold evidence of Aotearoa’s tangible and intangible history.

My PhD focuses on understanding coastal change at selected sites within Aotearoa over the past 1000 years and considering how future SLR will impact coastal archaeological sites. An interdisciplinary study where a three-pronged approach will adopt techniques from the disciplines of Mātauranga Māori, archaeology, and geomorphology. Successfully achieving this provides a range of exciting prospects. For example, what the distribution of archaeology means for understanding coastal change, what archaeology is at risk from SLR and how pūrakau (myths) link to the broader understanding of coastal change. The challenge, then, is to meaningfully design a research programme that incorporates the methods of Mātauranga Māori, archaeology and coastal geomorphology.

Next steps

I hope my research will have two impacts. The first is nuanced and sensitive collaboration with the iwi and hapū related to my case study area Ngunguru, in Northland. I have started engagement with Te Waiariki and aim to refine the research by examining and re-examining the research with their input from the start.

My second aim is to increase awareness of the threat posed to archaeological sites and that it will inform effective adaptive climate change policy. I have been invited to and actively involved in a working group with the mission task to provide a national level of guidance and advocacy to address the effects of climate change facing Aotearoa’s cultural heritage. Hopefully, by engaging with policy makers and government officials during the early stages of my PhD it will enable effective communication of the threats posed to archaeological sites.